PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY - Seneca

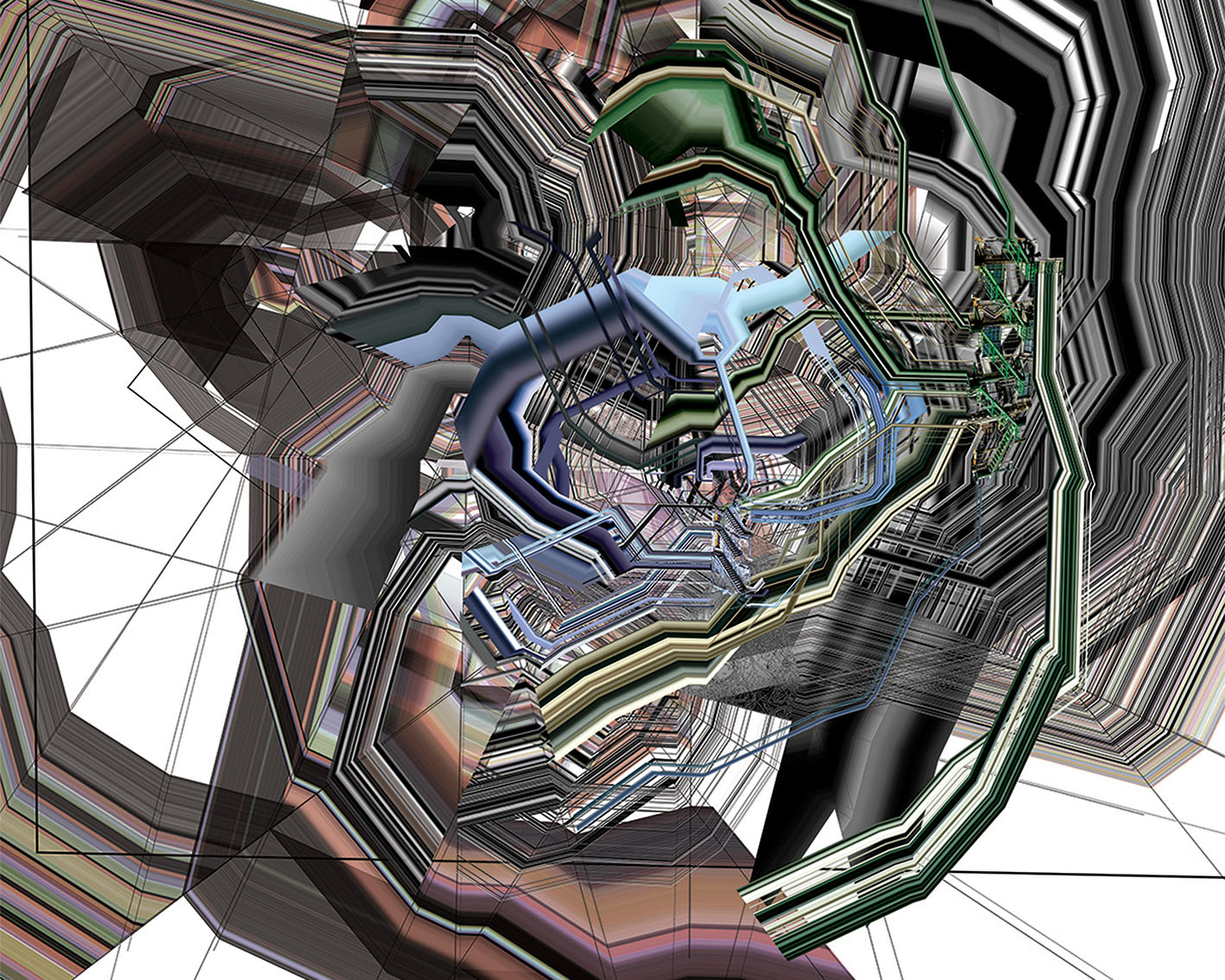

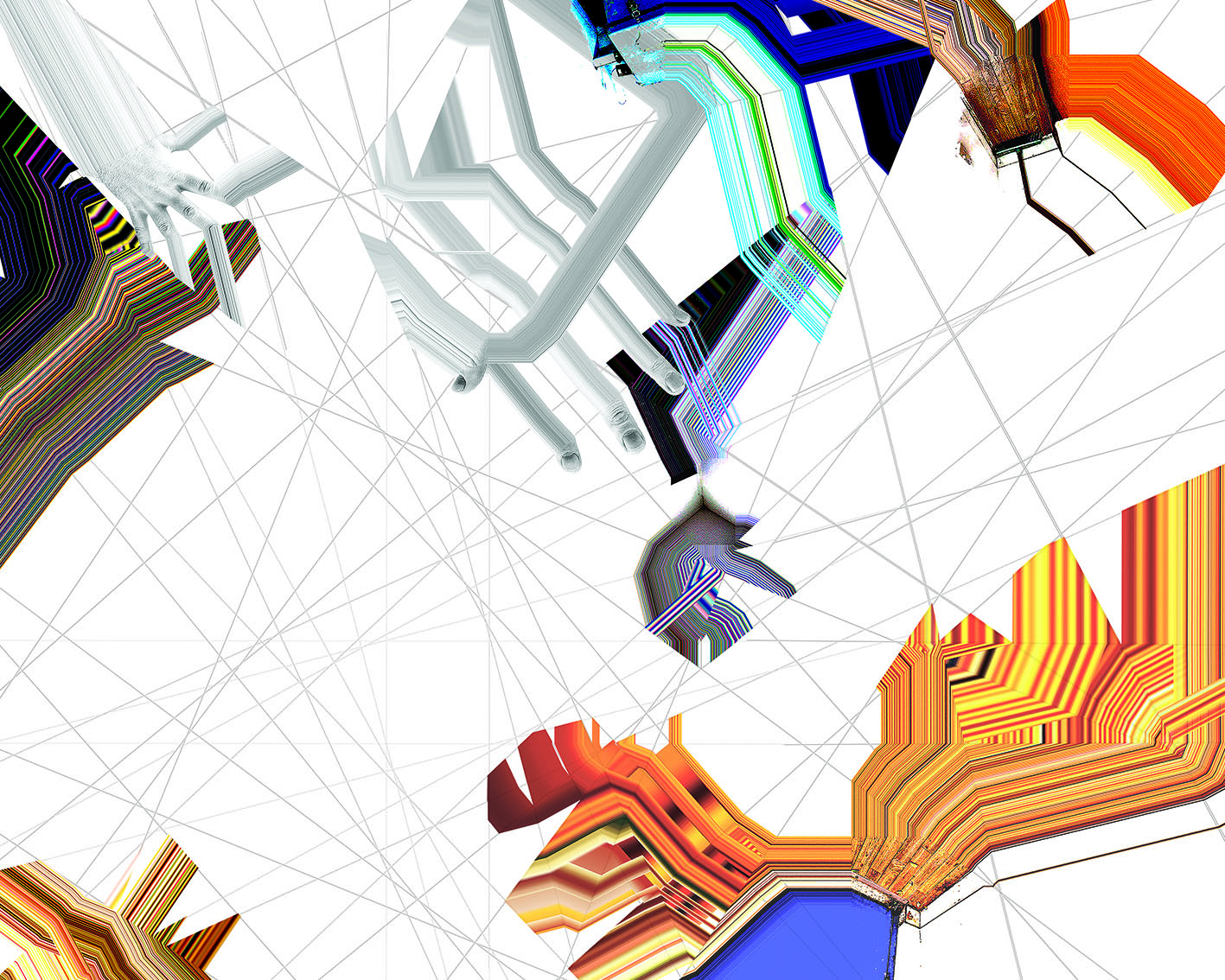

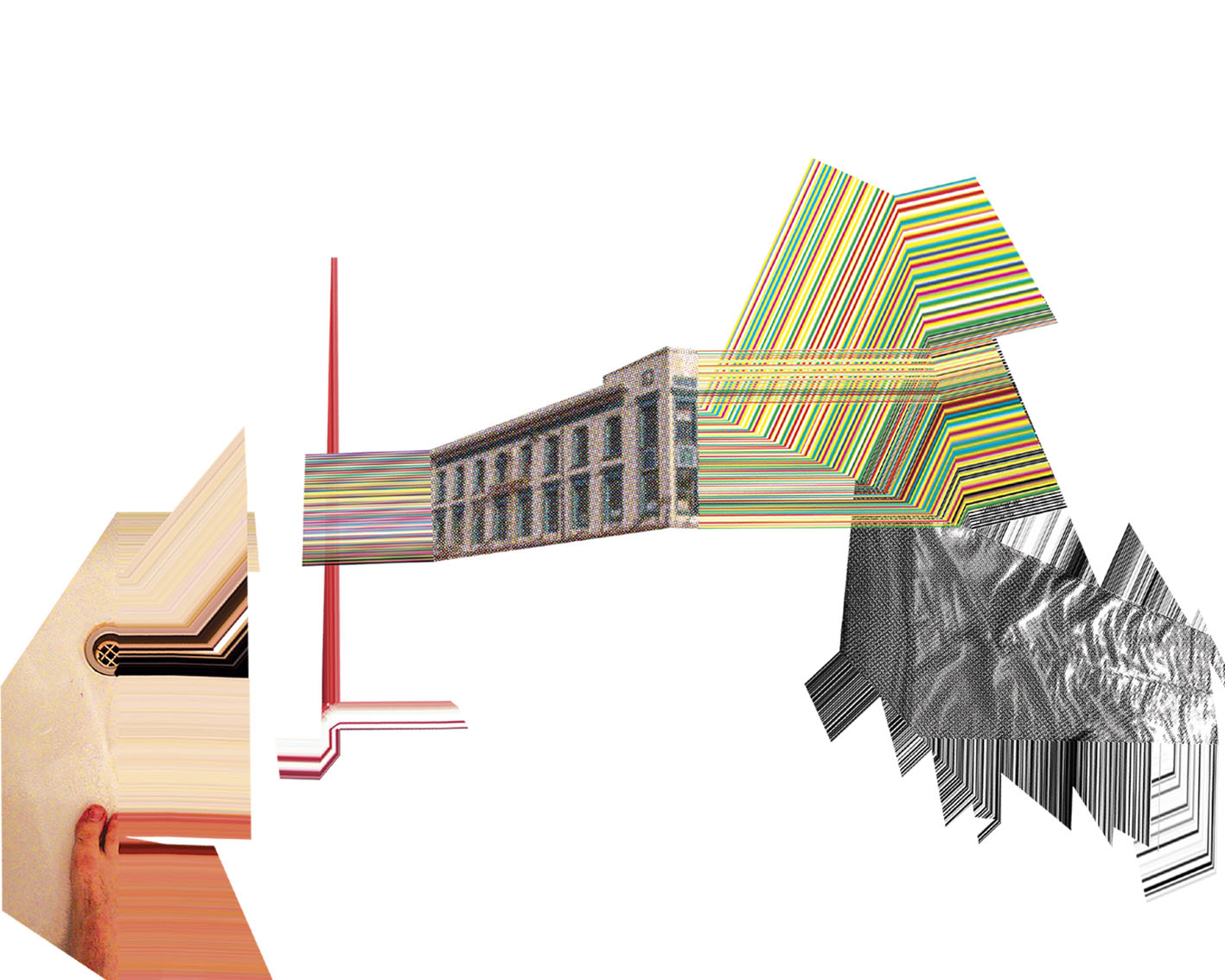

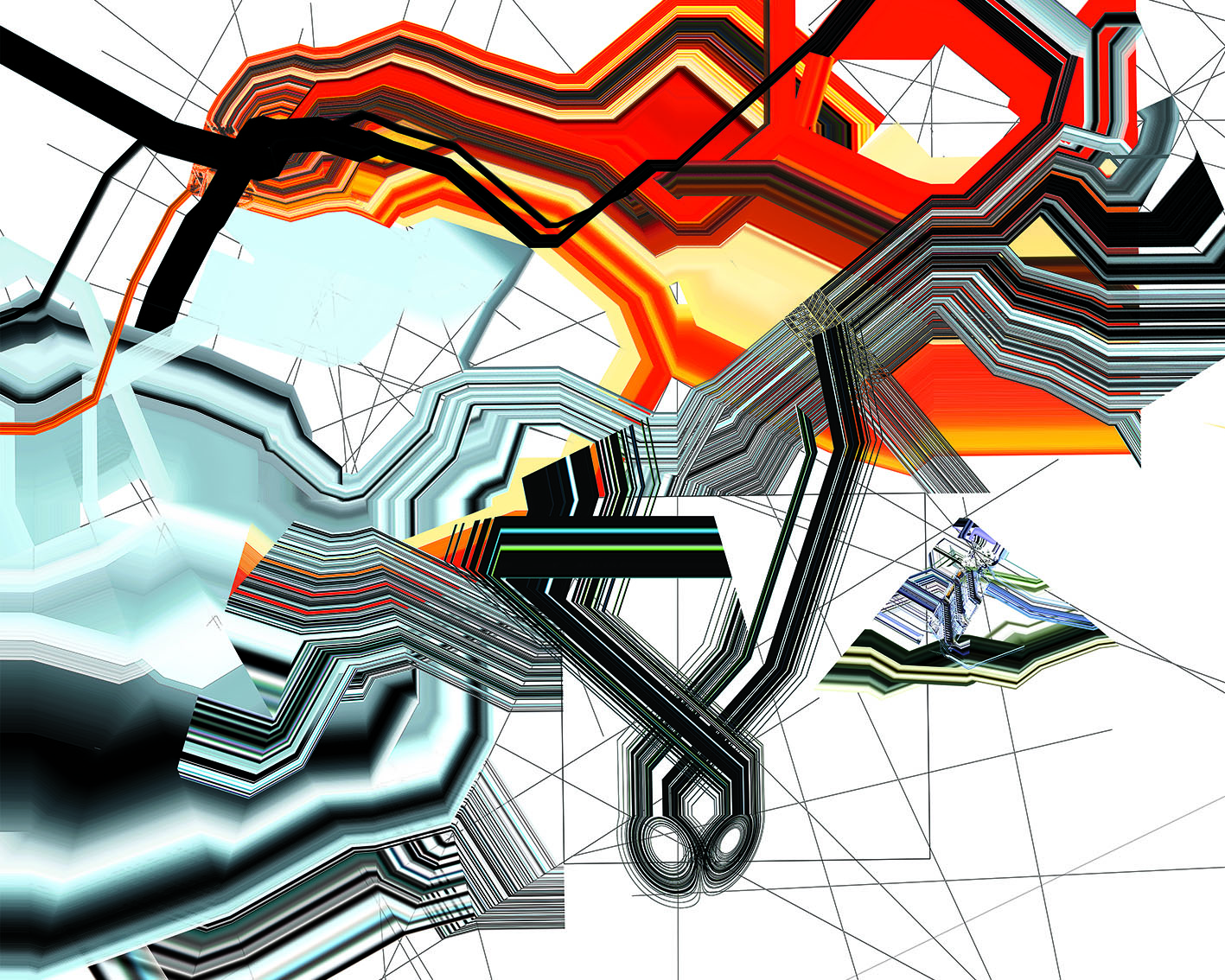

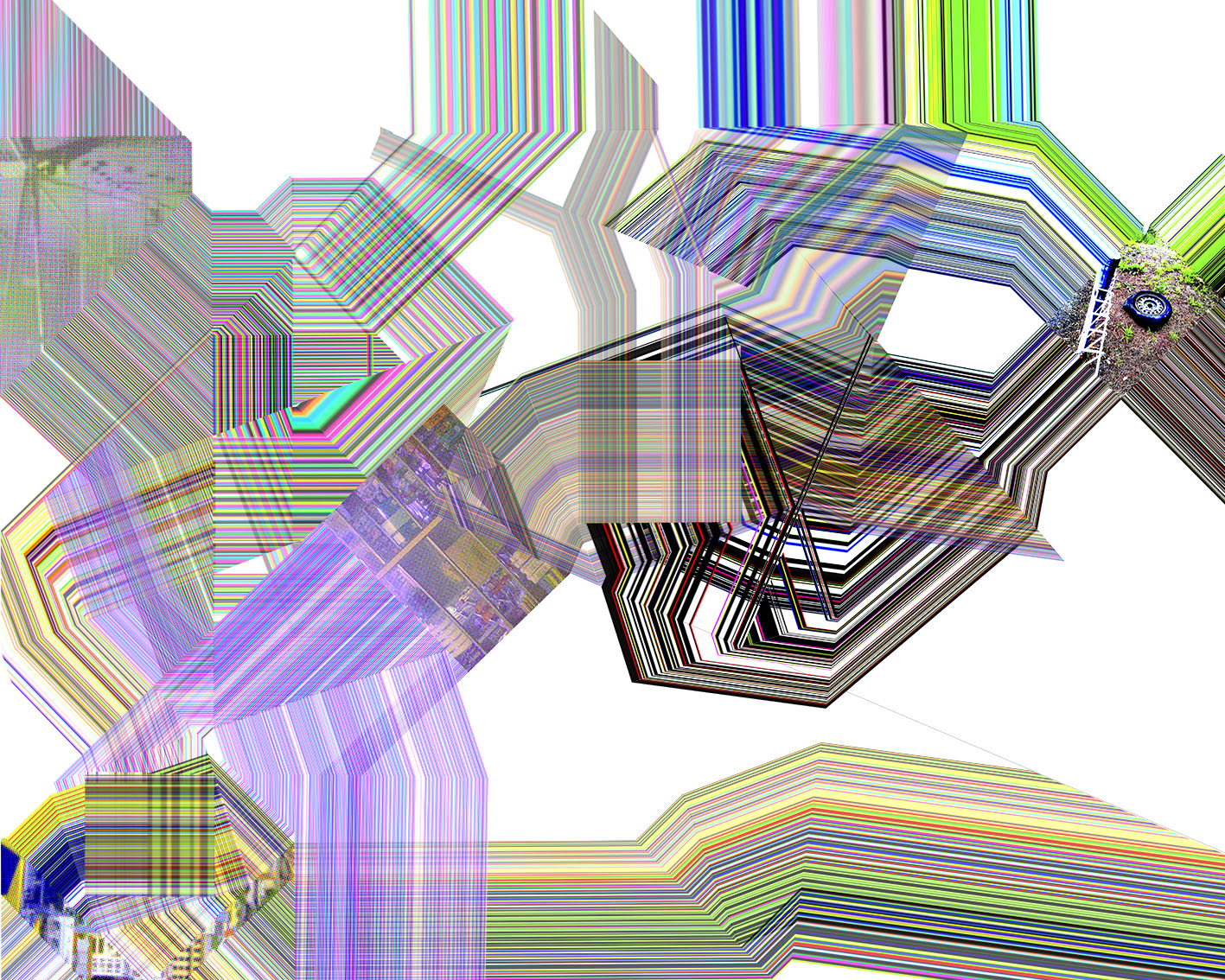

I accumulate photographic imagery as a form of data collection. I take this data and extract components, such as pixels, and then stretch and warp the components through a filter.

The destruction of the image as a generative strategy is a response to a personal narrative. Patterns emerge, there is order within chaos within order, and things are gained and lost.

In this story you take a trip. But don’t worry—you won’t get lost. You have a map. You have coordinates. You’ve been this way a thousand times before.

Your trip doesn’t begin when the sun comes up. Things don’t begin abruptly. Your trip begins in irregularly dispersed micro-starts. You think each one will be the last start you’ll have today, until it is.

Sometimes it’s a white cat that wakes you. Most times. That white cat comes and goes. Your dog doesn’t seem to notice, but you suspect your dog maintains a posture of respectful ignorance.

The white cat brings old dead corpses of animals, unasked for and unwelcome, at inconvenient times. The same corpses.

Your stomach light, you begin in earnest.

There are eight corners to your room. Just like the rest, unfortunately. That means 24 surfaces meet in eight nexuses.

You see, the thing is—it’s familiar only in the way every room with eight corners and 24 meeting planes and eight nexuses is. It’s never your room. Other people have rooms. You have the same eight corners and 24 meeting planes. The familiar becomes the unfamiliar easily.

And that fucking white cat is hanging around. He’s brought you a week-old dead thing.

You go to the bathroom. The bathtub—you never use it. It reminds you of a story. Seneca the Younger, attempting to cut his wrists in a tub after pressure from that wretch Nero. He must have thought himself a failure, Old Seneca Junior. His one great task, failed. And he can’t cut his wrist. The flesh is too old, the veins won’t bleed enough. Yeah, that story.

You like the components of that story. There’s a tub. There’s, you imagine, a dank room. You image warm water. The components bleed onto the day.

You shower, you leave. You can’t stop, because there’s no distinction between interior and exterior. Only things that stop you falling and stop you walking forever. Somewhere between your shower and finalising your ready-getting, and transferring from one side of your front door to the other side, five degrees lower than where the white cat is hanging out, blowing kisses, you remember David Malouf’s story. You remember An Imaginary Life and in your head quote it: ‘Do you have wings? Do you fly?’

And so you walk. And you drift. You are in Fitzroy North. You like its components. Different hues, shades. Too safe at times, too many faces. You wish you could break them down and make a quilt. You think about history, like you always do. You don’t like the rapid onslaught of gentrification. For financial reasons, you see. It will be time to go soon. But you’re happy for people who have comfort. Other people’s happiness is a lovely thing. You like the angles of artificial structures. You don’t like babies. You like money and you don’t like money. Because the gap between the realness of money and the hallucination of money is vast, those two components pulled apart and stretched at their basic atomic level.

But it’s easy to be like that. You are privileged, after all. You remember Seneca.

158 vertical lines. 86 horizontal. Today you chose not to notice the other ones. You see, sometimes the diagonal ones are unimportant. They are just horizontal lines trying to move ahead in the world.

Upstarts.

The security monitor at the entrance of the supermarket has been cracked. You like cracked plasma screens, they tartan. You document this and add it to your swelling collection of photos of cracked tartan plasma screens. You like how bright supermarkets are. Imagine a dim supermarket! Sometimes the only thing that wakes you up is the tinny glare of ugly shops. The white cat stalks. He heard your thoughts about wanting wine.

And you remember that story you heard. A truck driver back in the day. As truck drivers can be, he was partial to a bit of chemical assistance in staying awake. So partial and casual about it, in fact, that when a dose of speed was less than pure, hallucinations appeared. A mix of lack of sleep and unwanted ketamine. And so it was that in the desert, on his way to Broken Hill, he saw an elephant walk onto the road, thought, ‘Well, that’s clearly drugs’, and continued driving. The next thing he remembered was waking up in a hospital. What happened? He hit a goddamn elephant is what happened. Escaped from a circus in Broken Hill.

You begin to remember every story. You can remember every story you’ve ever heard. You can’t remember your own, though. The one about Jimmy Page abducting a 14-year girl—no one EVER talks about that one. The one about Peter Kocan, who tried to shoot Arthur Calwell point blank, went to an institution for the criminally insane, wrote a book, got a PhD and lectures English. You like the components of that story.

Where does the story go? Too many elephants.

METAPHOR

You are brushed with a by a deep daily sadness.

The thing is, you know the future. Everyone does. Everything cools down and homogenises.

Before you know it you’re on a street containing stones, 2362 of them. Less diagonal lines here. Just as well. Now you reach grass. Grass!

You may seem like you’re lost, BUT NO! You know exactly where you are. You’re somewhere between Seneca and a dead elephant. Some call it Edinburgh Gardens.

The white cat makes an appearance. Reverse-Cheshire, quietly judging your worth.

And you break down your ‘worth’ to its most basic components—the thoughts of others, the effect of your actions, the long term and short term, the subjective value of your so-called values—and you stretch them across, like DNA to Jupiter and back.

They criss-cross and you get to where you’re going. You’re drunk, there’s a white cat, and he’s laid an eight-year-old dead thing at your feet.

Macro-stories are the summation of micro-stories, and your sense of worth is as fragile, free and ultimately unimportant, as a truck-driver’s confidence in the falseness of runaway elephants.

You see, on a long-enough timeline, all the components of all the things, around you, and in you, stretch and fade, and macro-stories shrink into micro-stories to fill macro-stories. And thinking about this great endeavour, this great map of things, you are free. You can fly.

But don’t worry—you won’t get lost. You have a map, you see. You have coordinates. You’ve been this way a thousand times before.